This month's health bulletin focuses on:

- The measles epidemic in Samoa

- The ongoing Ebola outbreak in the Democratic Republic of Congo

- The plague epidemic in China

Samoa

The emerging news of a large measles epidemic in Samoa is receiving global attention. From a population of only 200,000 individuals, there have already been 4,000 cases. It is particularly tragic that over 50 people have already died, the vast majority under four years of age. In most outbreaks of infectious disease, the cause of the epidemic is often difficult to unearth. Here, the genesis of the outbreak is painfully clear. Painful, because this epidemic follows one of the lowest uptakes of the measles vaccines in recent years. Although around 80% of the children were fully immunised against measles in 2013, in recent years this has plummeted to just over 10% in 2018. This fall in vaccination rates is chiefly attributed to two reasons: the efforts of anti-vaccination protagonists and a catastrophic mistake with giving vaccination shots, resulting in the deaths of two children.

The emerging news of a large measles epidemic in Samoa is receiving global attention. From a population of only 200,000 individuals, there have already been 4,000 cases. It is particularly tragic that over 50 people have already died, the vast majority under four years of age. In most outbreaks of infectious disease, the cause of the epidemic is often difficult to unearth. Here, the genesis of the outbreak is painfully clear. Painful, because this epidemic follows one of the lowest uptakes of the measles vaccines in recent years. Although around 80% of the children were fully immunised against measles in 2013, in recent years this has plummeted to just over 10% in 2018. This fall in vaccination rates is chiefly attributed to two reasons: the efforts of anti-vaccination protagonists and a catastrophic mistake with giving vaccination shots, resulting in the deaths of two children.

In July 2018, two young children were given the MMR inoculation in a Samoan clinic. Many inoculations come in the form of a dry powder that must be added to sterile water prior to its use. Adding water to vaccine powder is a very simple procedure. What occurred in the Samoan clinic is that a liquid anaesthetic agent was used to mix the MMR vaccine, instead of water. It was given to a first child, who passed away. Later that day, when a second child was due for the same vaccination, a second nurse gave an inoculation from the same vial of MMR, killing the second child. Both nurses have now received custodial manslaughter sentences in New Zealand. As the facts were uncertain following these catastrophic events, the Samoan authorities halted any vaccination for a three-month period. This in itself created fear about the safety of the MMR vaccine but following the efforts of certain online anti-vaccination proponents, few parents were confident to vaccinate their children.

At present, the local healthcare facilities are severely stretched. In the main hospital, for example, the usual intensive care capability is just for four patients at a time: only these patients can receive advanced therapies such as intubation and ventilation - where a breathing machine delivers high levels of oxygen to those with a severe lung infection. As it stands, there are now at least 14 such children being treated in this way, all on breathing machines. International efforts are being launched to support the Samoan health authority during this crisis. As measles vaccination is essential to protect those unimmunised, UNICEF are sending over 100,000 does of the MMR to Samoa. Furthermore, to strengthen local healthcare abilities, healthcare workers are being deployed to the island. For example, members of the UK Emergency Medical Team, a team of 13 British doctors and nurses, are flying to Samoa at present to support the Australian Medical Assistance Team who have been fighting the outbreak for the last fortnight.

Sadly, the Samoan measles outbreak is just one of many affecting many parts of the globe at present. The most devastating is the epidemic in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Although eclipsed by the ongoing Ebola outbreak in the DRC, measles has actually been responsible for substantially more deaths. Although the death rate from measles is far less than that attributed to Ebola, measles is considerably more infectious: an astonishing 250,000 people are thought to have been recently infected, resulting in over 5,000 fatalities. Most deaths follow the severe bacterial lung infection that can occur after the initial measles virus infection has occurred. It’s important to realise that even for those who have made a recovery from measles, many thousands will be left with neurological damage, severely affecting the patient’s prospects in life. Only vaccination can help protect populations from measles and its consequences.

Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC)

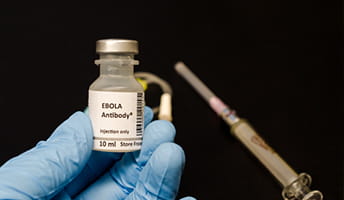

Ebola continues to recede in eastern DRC. Whereas up to 120 new cases of the severe viral infection were reported each week, less than 10 are now occurring. This is certainly a direct response to the continued efforts of the health workers in the field, reducing transmission through educating local communities, inoculating with the novel Ebola vaccine, and quarantining those infected. The fact that this has occurred in the face of persistent militia activity is a tribute to the healthcare workers’ bravery and perseverance. Although the effects of Ebola are reducing, the attacks continue, threatening to undo the work of those in the field. This Thursday, three healthcare workers and one resident were killed when the Mai-Mai militia attacked a base of the United Nations health agency in Biakato. This may have been linked to earlier warnings that health workers should leave or ‘face the worst’. Working under the shadow of such attacks and threats must surely make containing Ebola a herculean task.

Ebola continues to recede in eastern DRC. Whereas up to 120 new cases of the severe viral infection were reported each week, less than 10 are now occurring. This is certainly a direct response to the continued efforts of the health workers in the field, reducing transmission through educating local communities, inoculating with the novel Ebola vaccine, and quarantining those infected. The fact that this has occurred in the face of persistent militia activity is a tribute to the healthcare workers’ bravery and perseverance. Although the effects of Ebola are reducing, the attacks continue, threatening to undo the work of those in the field. This Thursday, three healthcare workers and one resident were killed when the Mai-Mai militia attacked a base of the United Nations health agency in Biakato. This may have been linked to earlier warnings that health workers should leave or ‘face the worst’. Working under the shadow of such attacks and threats must surely make containing Ebola a herculean task.

China

The infection caused by Yersinia Pestis, the plague, has been attributed with causing some of the greatest epidemics throughout history. Following bites by fleas from infected rodents, humans can develop painful, swollen glands termed buboes. When the infection is contracted in this way, bubonic plague is said to have occurred. Although still serious, this infection is more amenable to treatment than the pneumonic form of the illness. When the infection gets into the bloodstream and causes a lung infection, transmission increases dramatically: the cough that follows easily confers the infection to others. When this happens, pneumonic plague is said to be occurring. This form of the disease is not only more easily spread, but much more serious. For those who receive no treatment, the condition is universally fatal; even following treatment, 50% of patients still pass away.

The infection caused by Yersinia Pestis, the plague, has been attributed with causing some of the greatest epidemics throughout history. Following bites by fleas from infected rodents, humans can develop painful, swollen glands termed buboes. When the infection is contracted in this way, bubonic plague is said to have occurred. Although still serious, this infection is more amenable to treatment than the pneumonic form of the illness. When the infection gets into the bloodstream and causes a lung infection, transmission increases dramatically: the cough that follows easily confers the infection to others. When this happens, pneumonic plague is said to be occurring. This form of the disease is not only more easily spread, but much more serious. For those who receive no treatment, the condition is universally fatal; even following treatment, 50% of patients still pass away.

It is with good reason, therefore, that all outbreaks of plague receive urgent attention and fearful press reports. The present epidemic in Inner Mongolia, China, is small but persisting at present. The most recent infection was found in a rural herder in Siziwang county. He received treatment in a local hospital that has now seen four cases; both bubonic and pneumonic forms of the disease. The fear is that an infected individual may travel to a large populated city in China, where an epicentre of infection could result.

The history of the SARS virus (the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome) shows that this fear has been already realised in China this century. First identified in a farmer from Foshan county, China, only local SARS infections continued until one patient travelled to Guangzhou. From there it was only a matter of weeks until the virus had spread to Hong Kong, Vietnam, and Canada. The consequences should plague now be spread in this way are clearly of the utmost importance.